Our Spotlight series continues with Fiction alum Daniel Giovinazzo who shares with us how his practice of writing has evolved over time, the great influence his former mentors at the Lesley MFA program had on him, and how this has impacted his own work as a teacher.

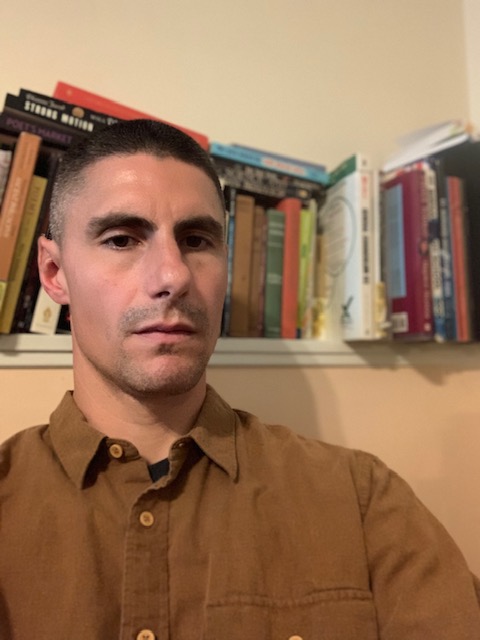

DANIEL GIOVINAZZO – FICTION, JANUARY 2011

DANIEL GIOVINAZZO works as a public educator and house-painter. He lives in Connecticut with his wife, poet Nikoletta Nousiopoulos, and their three children Rocco, Althea, and Dahlia. His work has been published in Bartleby Snopes, Burningword Literary Journal, The Caribbean Writer, Ethelzine, Indiana Voice Journal, and Pioneertown.

Interview By

Amy Jenness

We graduated from Lesley exactly ten years apart – you in 2011 and me in 2021. Without school deadlines or a specific project, I‘ve found it challenging to keep a disciplined writing practice going. Tell me about where you find inspiration and how you keep a writing life alive after Lesley University.

It’s complicated. I guess I’ve always had an affinity for writing. I turned out stories on my father’s clunky IBM before I understood that writing could be purposeful or useful. I decided I wanted to take writing seriously and there was some faking it at first, some necessity for an acute dream or some muse, all that. My process has changed since.

Much of the middle of my twenties was spent writing selfishly. I fought for two or three hours everyday– this took significant time away from friendships, relationships, media, career, money, whatever… From this experience, for whatever it’s worth, there’s a hard drive in my desk with over 1,000 pages of writing and poetry on it.

Then came where I am now: where I write religiously, but where writing is more of an observance, a reflection, an extension of myself– it’s just part of my person, I guess.

Some of what immediately motivated me to practice writing was the glamour on tv shows or movies involving writers, mass-syndicated best seller or prize-winning lists, false hope giving lit mag spam and such. Writing had a safe future in it it seemed, like: there’s some promise there, there’s validation there, there’s definitely people who’ll buy it, people who’ll be moved by it the same way other writers have moved me, etc. I don’t feel that so much now.

Currently, with now having taught writing since 2015, writing and opening up a paint can are synonymous: I can just pick up a pen and go. I have three children four and under, so I, as Steven Cramer told the entire residency one cold January night, ‘get up earlier and stay up later’.

Lastly, it would be impossible for me to keep a writing life without the support of my wife, poet Nikoletta Nousiopoulos, whose brilliance I respect immensely and whose belief in me from our beginning has propelled me further in my life now than I thought I’d ever be.

When did you know you wanted to write?

I knew my father the first thirteen years of my life– right now I’m thirty-seven. My father went from being one of the most important people in my life to one of the most important people not in my life, if that makes sense.

I know that storytelling, when done right, can be immortalizing. Maybe I started writing seriously to stop time, I’m not sure. I began my writing journey long before I took Steven Cramer’s craft seminar on reading like a writer, where I was introduced to Frank Conroy’s memoir.

Was there a moment during your Lesley experience that triggered a big aha moment that changed how you write?

A.J. Verdelle.

A.J. Verdelle had me paw through an entire Basic Grammar and Usage Workbook after my first submission– it was embarrassing and humbling and needed. Syntax now is my only honest friend.

A.J. always had me doing crazy things. One semester A.J. told me to ask faculty members for book recommendations– which became: Goodbye Columbus by Philip Roth, Someday This Pain Will Be Useful To You by Peter Cameron, They Came Like Swallows by William Matthews, Confessions of Felix Krull, Confidence Man and Tonio Kroger by Thomas Mann, Jesus’ Son by Denis Johnson, and Dylan Thomas’ Portrait of the Artist as a Young Dog.

The Good Negress has always been a very influential text for me. I read the book several times while working with A.J. We didn’t talk about her work a whole lot, but it was always cool to be close to someone whose work I respected so much.

I walked off the kitchen line at the Biltmore Bar and Grille in Newton and into the writing program at Lesley. I wasn’t taking good care of myself then and had been working double-shifts six days a week for about a year. Yeah, I definitely read Bourdain’s Kitchen Confidential a couple times that year. A.J. immediately saw some potential and gave me an honest chance to prove myself. A.J. has always tried to understand me. Ultimately, A.J. taught me everything I know about how to be a writer. She taught me that the quality of my art is less than or equal to the quality of my reading. A.J.’s words, “Reading is fundamental,” are still lucid and still push me to read more than write. There I found writers like: Richard Russo, Aimee Bender, Octavia Butler, Richard Wright, Jonathan Franzen, Ta-Nehisi Coates, David Foster Wallace, Zadie Smith, Charles Bukowski, Italo Calvino, Kurt Vonnegut, Fyodor Dostoevsky, Don DeLillo, William Gaddis, Langston Hughes, Claude McKay, Sylvia Plath, Roberto Bolaño, Lorraine Hansberry, Claudia Rankine, Franz Wright, Virginia Woolf, Suyi Davies Okungbowa, Evie Shockley, Anne Sexton, Atwood, Dickinson, Faulkner, Hemingway, Dick, London, Dostoevsky, Milton, Kafka, Kierkegaard, Sartre, Descartes, Morrison, Shakespeare, Sophocles, and more.

Portrait of the Artist as a Young Walrus and Bingo Under The Crucifix by Laurie Foos also had a major influence on my writing style. I can’t shake the absurdity of the image of the spiderman fiend turned giant baby– it’s so out there, but it means so much when it comes to responsibility as a metaphor.

I worked with Laurie Foos for one semester and learned that it’s okay to move between super-real, real, and surreal. This encouragement helped me develop range in my voice.

You teach English in the Groton, Connecticut public schools. Have you borrowed any lessons or approaches from your Lesley experience to guide your students?

We try to read all kinds of literature in and out of the canon, we try to debate and discuss ideas, values, and truths, and the English language. We all get to know each other; we try to have fun; mostly, though, the objective includes every student doing some reading and writing every class block. “Reading is fundamental” when it comes to literacy at any grade level, so all of my core English classes start with 15 minutes of independent reading, followed by a written response to a relevant question.

Also, reading as an entry point to both academic and creative writing has been useful when working with students. We have more ideas about a book we’ve actually read, or, at least, tried to read.

Useful approaches and lessons from the Lesley experience came directly from instruction during the low-residency cohort, including: Thomas Sayers Ellis’s seminar on imagery, Michael Lowenthal’s seminar on clock-watching, Laurie Foos on fabulism, A.J. Verdelle on revision, and Janet Pocorobba’s ‘open mic’ elective.

How much of your fiction writing comes from your life?

No matter how thinly veiled or allegorical my work is — all of my writing comes from my life experience. Writing is experience, thus all writers have is experience and words: truth and beauty. The trick, for me I guess, isn’t being interesting but presenting experiences in interesting ways.

Two of your short stories have writing or writers as the main theme – A Letter To A Famous Author (published in Pioneertown) and John Gardner Story. They both have a manic, stream-of-consciousness narrative and are visually striking on the page. This is actually two questions: Tell us about the tightly wound tone of those two stories. And, tell us about your decision to break up the text using different font sizes, long lines of dots, tabbed spaces between words in A Letter To A Famous Author. And, your use of poetry, time stamps and dialogue at the end of John Gardner Story.

Those stories are voice driven. Character drives and I try to stay true to character.

Stories are layered. Aesthetics are the most superficial layer, and often the most overlooked when it comes to prose. Sometimes evoking a visual element is a gut reaction. What you see on the page first is both prominent and immediate. As Norman Mailer wrote, writing is a ‘spooky art’.

I was first exposed to these kinds of forms in Jonathan Safran Foer’s Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close, though I have since studied House of Leaves by Mark Z. Danielewski and The Maximus Poems by Charles Olson.

Your stories “The Picture Worth Almost 3,000 Words” and “Wasps Swarm Before Death” capture the details of a small family. Is that an easy dynamic to capture or difficult?

Stories existing in a domestic domain are both easy and difficult for me to write. My experience has taught me that familial relationships, life-lasting or ephemeral, can be the most real — ‘real life is stranger than fiction’, though. The difficult part is sifting truth from that pool of emotion and getting it neatly on the page. The paradox here is: the writer must be just close enough and just far enough to give it real meaning — I’m not quite sure I have figured that out.

What are you working on?

I have a complete draft of a novel, Moody Street. The germ of which I penned in 2004 at Hartwick College under the guidance of Robert Bensen, the first person to encourage me to write seriously and unapologetically.

Moody Street deals two narratives. One follows the protagonist, Jay Caruso, chronologically from boyhood to adulthood, the other tells the jarring stories of Jay and his clique, attempting adulthood. Much happens in the vein of Encyclopedic human experience. The book ends where it begins, at Today’s Bar and Grille, to show the impermanence of time and experience. Growth is found infinitely in rebirth.

I finished a draft in 2010. After a ten-year hiatus, I went back to the book and began writing about the characters in adulthood. This gave me the idea to disjoint the narrative arc by alternating between the characters as adolescents and adults, giving the actual voices an organically different sound and style, a reflection of my inherent youth and growth as an artist.

Right now I’m looking for an agent/publisher.

Listen to Daniel read an excerpt from “Notes from the Slush Pile at the End of the World.”

Comments are closed